The SOPs and FCTM are crystal clear:

A go-around must not be initiated after selecting reverse thrust.

And yet… it keeps happening.

Airbus says about one A320 go-around a month is attempted after reverse is deployed!

This week, we look at what happened when one crew did exactly that - and came close to losing control.

CASE STUDY

✈️ WHAT HAPPENED

An A320 with CFM engines was on an ILS approach into Copenhagen using CONF3.

Visibility was good, but there was a 25-knot crosswind from the left with gusts up to 31 kts

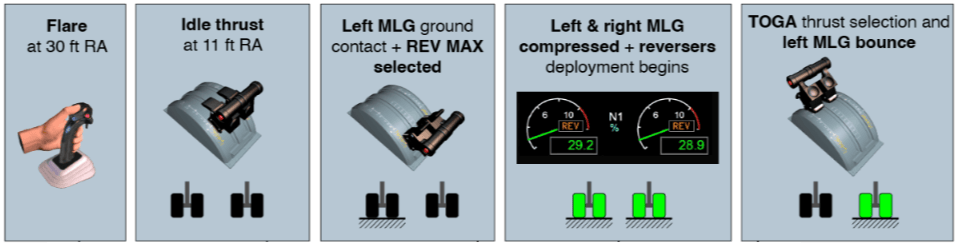

At 30 feet, PF started the flare.

De-crab began at 24 feet and thrust levers were set to idle at 11 feet.

Here's where it gets interesting…

The left main gear touched briefly - but wasn't fully compressed when the crew selected maximum reverse thrust.

A few seconds later, both mains compressed properly.

Weight-on-wheels triggered and by design the thrust reversers began deploying.

Then the aircraft bounced (fig 1)

Fig 1. Aircraft bouncing

The left gear uncompressed again, and with the aircraft attitude not feeling right, the crew called for a go-around and TOGA was selected.

Fig 2. Initial order of events

Engine 2 spooled up normally to TOGA thrust.

Engine 1 however stayed at idle with the REV indication still showing on the EWD.

The aircraft started veering to the left and the PF applied right rudder.

Both gears compressed again, then lifted off.

The aircraft continued drifting left.

At this point "ENG 1 REVERSE UNLOCKED" appeared on the ECAM and the beta target on the PFD disappeared.

The aircraft overflew the left runway edge with just a few feet clearance.

Fig 3. Aircraft veers to the left

Gear up was selected and the aircraft climbed on a trajectory about 20° left of the runway centerline.

When the gear retracted and pitch reached 12.5° — the target for single-engine go-around — vertical speed finally hit 1,000 fpm.

Fig 4. Continuation of events

Fig 5. Aircraft flying past glideslope antenna well left off the runway

THE SHUTDOWN

After dealing with the initial control issues the Engine 1 thrust lever was set to idle at 360 feet.

At 1,260 feet, Engine 1 was shut down as per ECAM procedures.

The beta target reappeared, enabling proper rudder trim and also autopilot engagement.

A second ILS approach was flown, and the aircraft landed manually with Engine 1 inoperative.

At the gate: three of Engine 1's four thrust reverser blocker doors were found to be deployed and unlocked (fig 6)

Fig 6. Reversers Eng 1 after landing

ANALYSIS

🤔 WHY IT HAPPENED

OK… that all sounds quite exciting.

But why did this actually happen?

Why didn’t the reversers stow on Engine 1 and what could the crew have done differently?

THE SYSTEM LOGIC

On CFM56 engines when you move thrust levers out of the reverse sector, each engine's ECU has to make a decision:

Are we on the ground or in flight?

Ground = stow the reversers. Flight = leave them deployed!

The ECU gets this information from the Landing Gear Control Unit (LGCIU). With the left and right systems working independently.

HERE'S THE PROBLEM

At the moment TOGA was selected, there was a tiny timing difference between the two ECUs:

Engine 2 ECU: "Both gears compressed → we're on ground → send stow command → spool up to TOGA"

Engine 1 ECU: "Left gear uncompressed → we're in flight → don't stow → stay at idle"

This millisecond difference happened because:

The thrust levers weren't perfectly aligned when moved from REV to TOGA

There's a slight delay in the signal chain: LGCIU → EIU → ECU

The left gear was bouncing at exactly the wrong moment

THE CASCADE EFFECT

With Engine 1 stuck in reverse:

😶 Auto-idle protection activated (preventing thrust increase)

😶 Beta target disappeared from PFD (EIS logic flags it when reversers aren't stowed)

😶 No rudder guidance for the pilot

😶 Massive asymmetric thrust moment and degraded climb performance

The A320 systems assume that once reverse is deployed, you're committed to landing.

When crews violate that assumption, they enter territory the aircraft wasn't designed for.

Fig 7. System logic flowchart showing ECU decision process

Airbus studied this across all engine types and aircraft families.

Only A320s (and A340s) with CFM56 engines can experience this issue.

Other engine types and aircraft have different reverser stowing logic that prevents this scenario.

OPERATIONAL CONSIDERATIONS

✈️ WHAT IS AIRBUS DOING ABOUT IT?

Airbus isn't just saying "follow the SOPs" and walking away.

They analysed 3.4 million flights from 31 operators and found one go-around per month after reverse selection across the A320 fleet.

That's significant exposure for something the manuals explicitly prohibit.

SOFTWARE UPDATES

An enhanced ECU software update is coming for CFM56 engines.

The new logic will prevent this scenario even if crews attempt a go-around after reverse selection - It should be out at some point in 2025.

EIS 2 software will also be modified so the beta target stays visible even when reverser doors are unlocked.

This gives pilots rudder guidance during the critical phase - instead of a flagged display when they need it most.

DOCUMENTATION CHANGES

The SOP language is moving from FCOM Layer 2 to Layer 1 — making it much more visible to crews:

"Select reverse thrust immediately after landing gear touchdown"

"As soon as reverse thrust is selected, perform a full-stop landing"

✈️ WHAT CAN WE DO ABOUT IT!?

STICK TO THE SOPS

The simplest answer: don't initiate a go-around after selecting reverse thrust.

Once those thrust levers go aft of idle, you're committed to landing.

Of course it’s not quite that simple.

THE HUMAN FACTOR

Another crew faced a similar dilemma.

This time miscommunication led to one pilot selecting TOGA while the other had already engaged reverse thrust.

The result?

Startle, confusion, and thrust levers cycling between TOGA and REV MAX before finally committing to land.

The aircraft came to a halt approximately 340 m before the end of the runway.

IN CLOSING

The SOPs exist for a reason.

These incidents show what happens when aircraft systems encounter scenarios they weren't designed for.

The Copenhagen crew did an exceptional job managing an impossible situation - asymmetric thrust, no beta target, degraded performance, all at low altitude.

But the real lesson is simpler: don't put yourself in that situation.

Make your go-around decision early. Once reverse is selected, you're staying on the ground.

Airbus is fixing the systems to prevent this scenario, but good airmanship means not relying on those fixes.